Juan Lago y Abel Fuentes mantuvieron una amena conversación con Russel Pope, el responsable del sonido en directo de Supertramp entre 1971 y 1983, sobre la historia del grupo y otras muchas cosas más.

TLW: Según mis notas, naciste en Johannesburgo (Sudáfrica), el 9 de Mayo de 1948... ¿Es correcto?

RUSSEL: Sí, no pude elegir... De haber podido hacerlo, habría nacido en Liverpool unos años antes.

TLW: ¿Estudiaste algo relacionado con la música o la ingeniería de sonido durante tu adolescencia?

RUSSEL: Me convertí en un adicto a la música en 1956, cuando ese personaje llamado Elvis apareció en escena. Formé parte de una banda que versionaba a otros artistas en Sudáfrica, por lo que aprendí algunas nociones básicas sobre sonido. Pero jamás me imaginé que acabaría dedicándome a ello, así que no presté demasiada atención.

TLW: ¿Cuándo te marchaste a Inglaterra?

RUSSEL: Llegué a Londres el día de San Valentín de 1970, con la esperanza de conocer y quién sabe si trabajar con los Beatles. Pero ellos se separaron casi de inmediato, así que tuve que cambiar de planes.

TLW: ¿Cuándo entraste en Supertramp?

RUSSEL: El 28 de Diciembre de 1970. Rick y Roger compartían un piso de mala muerte en Maida Vale, al oeste de Londres. Ni siquiera tenían muebles, sólo un par de camas. Richard Palmer acababa de dejar el grupo por alguna razón que yo no llegué a saber, y Bob Millar se marcharía poco después. Aquel fue el primero de los muchos momentos de película “Spinal Tap” que estaban por venir.

TLW: ¿Fue Davy O’List el primer sustituto de Richard Palmer como guitarrista?

RUSSEL: Recuerdo vagamente que Rick hizo alguna vez un comentario sarcástico sobre David O’List, así que si llegó a formar parte del grupo no debió ser durante más de cinco minutos. Richard Palmer ya se había marchado cuando yo llegué, y no debió ser una salida demasiado amistosa a juzgar por la tarjeta navideña que les envió y que yo leí mi primer día con ellos en el piso de Maida Vale. La tarjeta decía “Feliz Navidad, cabrones”.

TLW: ¿Entonces, quién se convirtió en el nuevo guitarrista del grupo?

RUSSEL: No había guitarrista. El grupo se componía de cuatro miembros: Roger Hodgson al bajo, Rick Davies al órgano, Dave Winthrop al saxofón y la flauta, y Bob Millar a la batería. Entonces Dave era el cantante principal, Roger sólo cantaba la tercera parte de las canciones y Rick no cantaba casi ninguna. Una formación muy extraña para una banda de rock, pero la cosa parecía funcionar aunque esa música no tuviese ninguna influencia sobre lo que el grupo llegaría a ser posteriormente.

TLW: Resulta un poco extraño que Dave fuese el cantante principal de aquella banda, cuando Roger era el vocalista de casi todas las canciones del primer disco... ¿Dave cantaba sólo canciones de Supertramp o también de otros artistas?

RUSSEL: Roger era el cantante principal del primer álbum, pero como grupo de cuatro miembros estaban muy limitados con lo que podían tocar en directo de ese disco. Muchas canciones de ese álbum eran demasiado preciosas y delicadas para tocarlas delante de un público lleno de tíos borrachos. Así que hacían versiones de otros artistas, como “All along the watchtower”, y también interpretaban “Try again” e “It’s a long road” del primer disco. Dave cantaba “Nothing to show” y las canciones de otros grupos, y parecía ser la fuerza dominante en el grupo por entonces. A lo largo de 1971, 1972 y los primeros meses de 1973 hubo unas cuantas canciones cantadas por Dave que se convirtieron en imprescindibles del repertorio. No se grabaron en ningún disco, pero aparecieron en algunos programas de la BBC como “Old Grey Whistle Test” y “John Peel Show”. Se trataba de “Black cat”, “White hot rock”... Un mundo totalmente distinto a lo que sería Supertramp más tarde.

TLW: ¿Cuándo empezó Roger a tocar la guitarra?

RUSSEL: Roger sólo empezó a tocar la guitarra cuando el álbum “Indelibly stamped” comenzó a tomar forma unos meses después, ya con Frank Farrell al bajo. Y también tardó mucho en empezar a tocar el Wurlitzer en directo, hasta que hizo su aparición “Dreamer”, la canción que se convirtió en la estrella de cada concierto durante los siguientes dos años.

TLW: Así que Roger se tomó su tiempo para empezar a tocar los teclados sobre el escenario...

RUSSEL: “Dreamer” era la única canción que Roger interpretaba a los teclados hasta que aparecieron “Hide in your shell” y “If everyone was listening”. Solía componer canciones con el piano y el armonio, pero nunca las tocaba en los conciertos. Escribió “Breakfast in America” en aquella época, pero sólo tenía una maqueta de la misma y nunca la interpretaba en directo hasta que decidió grabarla en 1979. Algo que ofendió profundamente la sensibilidad artística de Rick, que despreciaba esa canción. Por supuesto, económicamente a Rick le debe gustar mucho porque ha conseguido por ella los mismos “royalties” que Roger. Y todo por haber cantado esa frase tan inmortal: “What you got, not a lot”... Qué curioso.

TLW: ¿Por qué te uniste al grupo?

RUSSEL: Entré en Supertramp para ayudar a cargar y a descargar la furgoneta. Ni más ni menos. Me encontraba arruinado, sin calefacción y a punto de quedarme sin casa, y alguien dijo “¿Quién quiere irse a Noruega con un grupo de música por diez libras a la semana?”. Era toda una fortuna, así que me ofrecí voluntario... Quién sabía.

TLW: Así que participaste en la famosa “gira desastrosa” por Noruega... ¿Qué recuerdas de aquella gira?

RUSSEL: La tristemente célebre expedición a Noruega empezó el 28 de Diciembre de 1970, cuando cogimos el ferry que iba de Newcastle a Bergen. El primer concierto tuvo lugar el 30 de Diciembre en lo alto de una montaña, y allí casi todo el mundo llegó con esquís. Al final del concierto estaban todos borrachos dando gritos y empezaron a pelearse tirándose sillas. La furgoneta tuvo que quedarse en aquella montaña hasta la primavera de 1971, pues se averió por tener que subir unas pendientes tan empinadas. Alquilamos otra furgoneta y la gira duró unos diez días, en los que viajamos en ferry y por carreteras heladas a través de los fiordos con barrancos de trescientos metros a los lados. Hermoso y aterrador a la vez. Lo único que yo pensaba era “¿Dónde demonios me he metido?”.

TLW: ¿Disteis muchos conciertos en Noruega?

RUSSEL: Después de aquel infame concierto en la montaña, actuamos en el Auditorio de Bergen el 31 de Diciembre. Luego, durante más o menos una semana, viajamos hacia el sur, cogimos numerosos ferrys para atravesar los fiordos, cruzamos múltiples montañas, dimos un concierto en la isla de Haugesund, en una especie de establo gigantesco, y otro en algún lugar de Stavanger. Después recorrimos más montañas, cogimos más ferrys y al final tomamos un barco hacia Dinamarca, desde donde hicimos un gélido viaje por carretera hasta París, haciendo noche en Hamburgo y sufriendo un retraso digno de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en la frontera franco-alemana.

TLW: ¿Por qué viajásteis hasta París?

RUSSEL: Teníamos que dar un concierto en la Universidad H.E.C. Llegamos allí apenas cuatro horas antes del concierto, y Sam estaba como un niño pequeño, repitiendo una y otra vez la frase “¡Nos hemos graduado en H.E.C.!”. A partir de entonces, siempre que había un problema él decía “Sí muchachos, ¡pero os graduásteis en H.E.C.!”. Para ser sincero, yo estaba encantado de conocer París, aunque fuera en aquellas circunstancias, y me gustó especialmente la elección de restaurantes que hizo Sam, así como su tarjeta de crédito.

TLW: ¿Cuáles eran tus tareas en el grupo durante aquella primera época? ¿Es verdad que incluso conducías la furgoneta?

RUSSEL: Conducía la furgoneta, me congelaba en la furgoneta, dormía en la furgoneta, cargaba y descargaba la furgoneta, me encargaba de todos los cables, afinaba la batería, mezclaba el sonido, etc., etc., etc. Hice todo eso desde principios de 1971 hasta Septiembre de 1974, cuando salimos de gira con “Crime of the century” y ya teníamos un equipo de personal en condiciones y un presupuesto de verdad. Desde el verano de 1972, conté con la colaboración de un amigo que había estado en la misma banda de versiones que yo y que se unió a nosotros como ayudante mío. Se trataba de Tony Shepherd que, igual que yo, acabó dedicándose a tareas que jamás se había imaginado, en este caso a la iluminación de los conciertos de Supertramp. El y Roger fueron muy buenos amigos durante los siguientes treinta años, y lo mismo ocurrió con Ken Allardyce, que era el otro encargado de las luces en los conciertos y también acabó trabajando en algo de forma accidental.

TLW: ¿Habías trabajado como ingeniero de sonido con otras bandas antes de entrar en Supertramp?

RUSSEL: No, surgió sobre la marcha. Poco después de ser reclutado para conducir y transportar cosas, Mick Coles, el técnico jefe que me había contratado, anunció que se marchaba para ser conductor del bajista de Led Zeppelin, algo que aparentemente era un gran paso en su carrera. Así que las tareas de sonido recayeron sobre quien estaba más cerca de la consola de mezclas por entonces, y ese era yo.

TLW: ¿Recuerdas en qué época entró Dougie Thomson en el grupo?

RUSSEL: Por lo que recuerdo, Dougie se incorporó en algún momento de la primavera de 1972. Tal vez un poco antes. Roger era el bajista cuando yo entré en el proyecto, y después lo fue Frank Farrell, que formó parte del grupo desde “Indelibly stamped” hasta finales de 1971 o principios de 1972.

TLW: Según el libro “The Supertramp Book”, de Martin Melhuish, tú le recomendaste a Roger que tomase LSD cuando lo hizo por primera vez en Julio de 1972... ¿Es eso cierto?

RUSSEL: Nunca he leído ese libro. Un buen amigo me recomendó que no lo hiciera, y confié en él. Vi la portada del libro y sólo aparecían cuatro de los cinco miembros del grupo, a pesar de que se suponía que era el libro definitivo sobre la banda. Dudo mucho que haya un fan de Supertramp en todo el mundo que no se haya dado cuenta de que alguien, en alguna parte y de algún modo, decidió eliminar a Roger de esa foto. Tal vez eran muy malos en matemáticas, o simplemente se olvidaron de él.

TLW: En una carta que le envió a Sam en 1972, Rick escribió esto sobre ti: “Russel, nuestro fiel sirviente, podría abandonarnos pronto. Está trabajando en un proyecto increíble que le haría ganar incontables millones. Desaparece durante sus días libres para estudiar ‘el plan’. Va a encargar Coca-Cola por valor de 25.000 libras”... ¿Puedes decirme a qué se refería?

RUSSEL: Por supuesto, la palabra “sirviente” debería haberte dado la pista... Se trataba de un proyecto loco para abrir sitios de comida rápida en Inglaterra. Unas chicas con patines te servirían las hamburguesas, las patatas fritas y las bebidas en tu propio coche. Tony Shepherd, su primo y yo habíamos diseñado una bandeja especial que se acoplaba a la puerta del coche, pues Inglaterra no era California y las bandejas abiertas que se utilizaban en los Estados Unidos no funcionarían bajo la lluvia ni en los inviernos helados ingleses. Teniendo en cuenta la lluvia y los inviernos helados ingleses, se trataba de una locura, pero estábamos convencidos de que si Coca-Cola ponía su logotipo en nuestras bandejas podríamos abrir el primer local en seis meses y retirarnos al sur de Francia el mes siguiente. Así dejaríamos de ser sirvientes que conducían una furgoneta a través de las mojadas y heladas carreteras inglesas.

TLW: ¿Qué recuerdas de la época en la que estuviste viviendo con el grupo en el número 35 de Holland Villas, en Londres?

RUSSEL: Estuvimos viviendo en Holland Villas desde el 1 de Enero hasta el 1 de Julio de 1973. Anteriormente, en 1971 y 1972, Rick, Roger y yo habíamos compartido varios pisos en Londres con distintas mujeres, todas muy comprensivas, que siempre estaban dispuestas a pagar el alquiler. Pero esta era una casa enorme con cuatro dormitorios, demasiado nivel para lo que estábamos acostumbrados. Había un piano de cola, estatuas sobre sus pedestales y una larguísima y lujosa mesa de comedor. A cargo de la casa estaban un ama de llaves, Gladys, y un poco agraciado perro de la raza “beagle” al que llamaban ‘Droopy’ (‘Hundido’) porque tenía las patas tan cortas que su tripa estaba siempre prácticamente pegada al suelo.

TLW: ¿Cómo conseguisteis alquilar una casa tan grande, teniendo en cuenta que Supertramp todavía no había triunfado?

RUSSEL: El alquiler estaba a nombre de Maggie Charles, que era una de las modelos londinenses mejor consideradas de la época. Era la hermana mayor de Barbara Charles, que fue novia de Roger durante un breve período de tiempo y después se casó con Ken Allardyce, quien acabó uniéndose a nosotros como miembro del equipo técnico para encargarse de la iluminación de los conciertos junto a Tony Shepherd. Maggie Charles después se haría novia de Roger durante nuestra estancia en Holland Villas y mucho más tarde también se casó con Ken Allardyce. Ya sé que es un poco lioso, pero todo el mundo acabó contento con el resultado final de aquellos emparejamientos. Durante un tiempo, el departamento amoroso del grupo fue una especie de juego de las sillas musicales.

TLW: ¿Es verdad que Joe Cocker había vivido en aquella casa?

RUSSEL: Sí, los dueños le habían alquilado previamente la casa a Joe Cocker y su banda, y se habían quedado tan horrorizados que no querían saber nada más de ningún grupo de rock. Pero Maggie Charles, que era una modelo prestigiosa y una persona inteligente, consiguió convencerles para que le alquilaran la casa a ella y, supuestamente, a otras tres amigas suyas que también eran modelos.

TLW: Así que pagabais el alquiler como si fueseis cuatro personas, cuando en realidad vivíais allí muchas más...

RUSSEL: Enseguida llenamos las cuatro habitaciones: Roger y su hermana Caroline en una, Maggie y una ex novia y una futura novia de Roger en otra, Nigel y Nicky, que eran dos amigos australianos de Rick, en otra, y los Bollos, que eran dos gemelos australianos totalmente idénticos, en la cuarta. Rick vivía en el suelo dentro del vestidor del baño y Tony Shepherd, Ken Allardyce y yo, con nuestras respectivas novias, en el desván. Había una escalera desmontable sobre el techo del pasillo que conducía al desván, donde no había ventanas, ni baldosas en el suelo, ni nada. Teníamos tres colchones y dividimos la estancia colgando unos tapices indios de la época a modo de mamparas, para tener algo de intimidad. Así que en total éramos quince personas en la casa de Holland Villas.

TLW: ¿Y qué me dices del ama de llaves? ¿Era cómplice vuestra?

RUSSEL: Sí, Gladys nos quería con locura y se unió a nuestra conjura, igual que Droopy, que jamás había comido tan bien como entonces. Todos los meses teníamos que poner en práctica un elaborado plan cuando los propietarios de la casa llegaban allí para cobrarle el alquiler a Maggie y a las tres amigas que se suponía compartían la casa con ella. Había que hacer desaparecer cualquier indicio sobre todos los demás, incluyendo instrumentos musicales, sacos de dormir y sustancias ilegales, y había que colocar la escalera del desván en el techo del pasillo como si jamás se hubiera usado. En una ocasión, los dueños insistieron en que querían echarle un vistazo al desván y en apenas cuatro minutos tuvimos que desmantelar nuestro pequeño palacio y escabullirnos sin hacer ruido, mientras Maggie les entretenía con alguna excusa hasta que todo estaba despejado.

TLW: ¿Qué ocurrió dentro de la banda, musicalmente hablando, durante aquella época?

RUSSEL: Fue en ese período cuando llegamos al final de la segunda versión de Supertramp. En Semana Santa nos marchamos a Copenague para actuar varias noches en el Club Revolution. Creo que fue una semana, pero como era Pascua y Carlsberg estaba promocionando su cerveza de Pascua, dudo mucho que algún miembro del grupo sea capaz de recordarlo. Los daneses creyeron que sería divertido ofrecerles a los estúpidos ingleses su cerveza de Pascua, porque la proporción era más o menos de un coma etílico por cada dos cervezas. En el camino de regreso hacia Londres, Dave Winthrop anunció de repente que dejaba el grupo y desapareció en una cafetería de la autopista para no volver a ser visto jamás. Sin dar ninguna explicación. Supongo que fueron los efectos de la cerveza de Pascua. De vuelta en Holland Villas, recuerdo que Kevin Currie vino un día a llevarse la batería y hubo una gran discusión al respecto. Rick y Roger decidieron terminar cuanto antes con el sufrimiento de Kevin, y las cosas empezaron a quedar en suspenso dentro del grupo.

TLW: Así que parecía que Supertramp por fin se había desintegrado...

RUSSEL: Sí. Tony y yo empezamos a alquilar el viejo sistema de sonido de Sam, y a alquilar nuestros propios servicios. Pronto acabamos trabajando con Steeleye Span y nos marchamos con ellos a América para hacer una gira durante el mes de Julio junto a Jethro Tulll. En Los Angeles, junto al escenario del Forum, me encontré con Wilf Wright, el agente de Chrysalis que había organizado la mayoría de los conciertos de Supertramp hasta entonces. Me preguntó por el grupo y yo le dije que me daba la impresión de que se iba a separar. El me señaló con la mano las 20.000 personas que había allí y me dijo: “Eran una buena banda, pero por supuesto Supertramp jamás podría haber conseguido algo como esto”... Frases como esa se te quedan grabadas en la memoria. Pero cuando Tony y yo regresamos de los Estados Unidos a finales de Julio, Rick y Roger ya habían hecho algunos ensayos con Bob y con John, y la banda había resucitado.

TLW: Y poco después, a finales de 1973, todos os fuisteis a vivir a una casa de campo llamada “Southcombe”, para cambiar el destino de la banda...

RUSSEL: Sí, todos nosotros, incluyendo esposas, novias e incluso el gato de Dougie y Christine, que se llamaba TC. Fue una idílica fantasía invernal, con A&M pagando todos los gastos y nosotros encontrándonos en un lugar donde cualquier cosa era posible y sabiendo que todo iba a funcionar y a partir de entonces todos íbamos a ser felices. Y también era muy divertido salir a tomar algo al pub que había a una milla de distancia, caminando entre la nieve y las mierdas de vaca.

TLW: ¿Es cierto que el técnico de sonido Norman Hall también estuvo viviendo allí con vosotros, aunque todavía no era miembro del equipo?

RUSSEL: Sí. Norman no se uniría a nosotros hasta la primera gira, que empezó en Septiembre o en Octubre de 1974 en el Teatro King’s Road con una actuación especial para la gente de A&M. El había sido compañero de piso de Rick en Shepherd’s bush, y acabamos convenciéndole para que se encargase de la batería de Bob Siebenberg. Uno o dos años más tarde, se convirtió en mi “ayudante” después de que Kenny Thomson fuese ascendido a responsable del escenario y luego a responsable de las giras de Chris de Burgh. Mucho más adelante, Norman fue elegido ingeniero de sonido para la banda de Rick y Sue.

TLW: ¿Cuál fue el mejor sistema de sonido que usó Supertramp mientras tú formabas parte del grupo?

RUSSEL: Exceptuando los primeros tiempos, siempre utilizamos un único sistema de sonido con consolas Midas y altavoces Martin. Creo que conseguí la primera consola Midas que se construyó, en 1971, y después tuve otras tres a lo largo de los años. Con esa primera consola Roger y yo grabamos una maqueta completa de “Crime of the Century” en la casa de campo donde preparamos el álbum. El suizo Sam era quien ponía el dinero en aquellos años y era excéntrico hasta decir basta, pero también era muy generoso y adoraba el grupo y su música. Desapareció a finales de 1972, perdonándonos una deuda de unas sesenta mil libras.

TLW: ¿Por qué decidiste utilizar ese sistema de sonido en concreto?

RUSSEL: En 1973 vimos a Pink Floyd interpretar el álbum “Dark side of the Moon” en Londres y me quedé impresionado al escuchar un concierto de directo que sonaba tan jodidamente bien. Ellos también utilizaban consolas Midas, pero su sistema de altavoces Martin Audio era gigantesco. Así que cuando vi el presupuesto que había para la gira de “Crime of the Century” me fui directo hacia Dave Margereson y le dije “Quiero tener el mismo sistema que usa Pink Floyd, muchas gracias”. Ese sistema nos permitía reproducir el álbum en los conciertos con la impresionante potencia que esas canciones orquestales necesitaban para impactar al público a nivel visceral. Era muy caro, pero merecía la pena cada maldito penique que costaba. Más adelante algunos decidieron que debíamos gastar mucho más dinero en cosas “importantes” como viajes de avión en primera clase, estúpidas limusinas y estúpidos hoteles caros. Prioridades diferentes.

TLW: ¿Dónde funcionaba mejor ese sistema de sonido, en recintos cerrados o al aire libre?

RUSSEL: El mejor sonido siempre se daba en pequeños recintos cerrados, preferiblemente en auditorios y teatros. En ellos la acústica era muy similar a la de un estudio, bastante más apagada sin el montón de reverberaciones que producen los muros de hormigón y los miles de asientos de acero que conforman los grandes estadios. Los conciertos al aire libre podrían ser fantásticos, pero las leyes de la física te obligarían a utilizar una gran cantidad de potencia para compensar ese espacio abierto. Cuando los conciertos empezaron a ser de más de 50.000 personas, se hizo muy difícil mantener la enorme majestuosidad del sonido y seguir conservando un ambiente íntimo y cálido. Pink Floyd nunca tuvo ese problema porque su material era muy orquestal y un tanto abstracto. Pero Supertramp interpretaba muchas canciones pop cortas y tenían que sonar igual que en los discos porque eso era lo que el público esperaba escuchar. La mayoría de las veces la cosa funcionaba muy bien, pero de vez en cuando no tanto.

TLW: ¿Con qué productor preferías trabajar, con Ken Scott o con Pete Henderson?

RUSSEL: Ken Scott había trabajado con los Beatles y en los estudios de Abbey Road, aunque yo no sabía que procedía de “Beatlelandia” hasta que nos metimos en el estudio con él. Yo me había enamorado de “Hunky Dory”, el disco que David Bowie había publicado antes que “Ziggy Stardust”, y prometí que si alguna vez teníamos la oportunidad Ken Scott debía ser la primera y única elección para grabar “Crime of the Century”. Así que estuve incordiando a Dave Margereson durante meses hasta que consiguió traer a Ken para mezclar un single, “Land ho”, que no funcionó demasiado bien, por lo que casi desperdiciamos esa gran oportunidad. Por suerte, la maqueta que habíamos grabado en la casa de campo consiguió convencer a Ken, que se lo pensó dos veces y accedió a participar en el álbum.

TLW: ¿Por qué luego sustituisteis a Ken por Pete?

RUSSEL: Después de “Crime of the century” y “Crisis? What crisis?”, se decretó que hacía falta un cambio y le pedimos a Geoff Emerick , el ingeniero de “Sgt. Pepper”, que grabase “Even in the quietest moments”. Ya sabes, si tienes alguna duda piensa en los Beatles... Geoff no estaba disponible por entonces y nos recomendó a su alumno aventajado, Pete Henderson, para registrar las pistas de acompañamiento en el Rancho Caribou, hasta que Geoff pudiese ocuparse de hacer las mezclas finales en la Record Plant de Los Angeles. Pete acababa de grabar el disco “Wings” de Paul McCartney, así que nos pareció una buena idea. Voló hasta Los Angeles y nos encontramos con él en un estrafalario restaurante moderno del Cañón de Topanga. Nos quedamos un poco desconcertados al ver que parecía un adolescente, pero no hace falta decir que en diez minutos nos olvidamos de su aspecto físico y Pete se convirtió en parte de la gran familia Supertramp, relación que sigue manteniéndose a día de hoy.

TLW: ¿Cuándo dejaste Supertramp?

RUSSEL: El 25 de Septiembre de 1983, cuando terminó la gira de “Famous last tour”.

TLW: ¿A qué te has dedicado desde entonces?

RUSSEL: A estudiar los hábitos alimenticios de la ardilla de California. Y de vez en cuando, a ejercer de productor e ingeniero de algunos artistas independientes que me gustan.

TLW: En el verano de 2006, estuviste trabajando en los estudios Cups’N’Strings restaurando las cintas maestras del concierto en París de 1979... ¿Qué puedes contarnos sobre eso?

RUSSEL: Recopilé las cintas, distribuí las cintas, recogí el resultado digital de las cintas y le envié a Pete Henderson las cintas. Exactamente igual que en 1971: conducía el camión, cargaba el camión, descargaba el camión, etc. Fue como completar el círculo.

TLW: ¿Es verdad que esas cintas fueron encontradas en el establo de Bob Siebenberg y estaban cubiertas de estiércol de vaca?

RUSSEL: Quiero pensar que sí... Es una historia interesante y ha inspirado un montón de comentarios.

TLW: ¿Sabes por qué se encontraban allí?

RUSSEL: Bob “adquirió” un montón de cintas maestras que habíamos grabado durante la gira de “Breakfast in America” en 1979, y grabó encima de ellas cosas de sus propios proyectos en solitario. Sin embargo, nadie pareció preocuparse por eso ni pensó en el futuro. Yo llevaba mucho tiempo fuera del grupo, y Dave Margereson también.

TLW: Se dijo entonces que también habías trabajado sobre el vídeo de aquel concierto con vistas a publicar un DVD... ¿Es verdad?

RUSSEL: No.

TLW: ¿Crees que ese DVD podría ser publicado en breve?

RUSSEL: No sé nada sobre ese tema.

TLW: Roger Hodgson ha comentado recientemente que está dispuesto a volver a trabajar con Supertramp... ¿Trabajarías de nuevo con Rick Davies y con él si te lo pidieran?

RUSSEL: No creo que me lo pidan. En cualquier caso, los Beatles tienen más posibilidades de volver a reunirse que ellos.

TLW: ¿Sigues en contacto con otros miembros de Supertramp?

RUSSEL: No.

TLW: ¿Quién era tu mejor amigo en el grupo?

RUSSEL: La segunda consola Midas.

TLW: ¿Qué te parece que mucha gente se refiera a ti como “el sexto miembro de Supertramp”?

RUSSEL: Que me gustaría mucho que los contables del grupo dijesen lo mismo.

TLW: Eres un libro abierto sobre la historia de Supertramp... ¿Estás seguro de que no quieres escribir tu propio libro?

RUSSEL: Escribir ese libro podría resultarme hasta divertido, pero la verdad es que contaría cosas que a la mayoría de los fans no les gustaría leer. Y creo que provocaría cierto malestar entre determinados miembros del grupo. Así que tengo muchos apuntes, pero no tengo intención de publicar nada. Siempre he dicho que sólo debe haber diez personas en Canadá y otras tres en Francia que estarían interesadas en leerlo.

TLW: ¿Por qué piensas así?

RUSSEL: Supertramp nunca tuvo una estrella en el sentido convencional de líder de banda de rock, así que eran una especie de grupo anónimo. Y los demás siempre tuvieron miedo de que Roger fuese el centro de atención, así que hubo un esfuerzo importante en intentar evitar cualquier culto personal. Ser relativamente anónimos siempre les protegió de líos sobre quién era quién, quién le hizo algo a quién y todos esos asuntos que suelen aparecer en el trasfondo de un grupo con tanto éxito. Y sin consumir heroína, sin destrozar habitaciones de hotel, sin tener escándalos sexuales... No es que tomasen sólo leche con galletas, pero se apartaban del comportamiento libertino habitual y por tanto eran extremadamente aburridos para el público. Pero todo el mundo ha visto la película “Spinal Tap”, así que lo único que hay que hacer es cambiar los nombres y ya está.

TLW: Pero el legado musical de Supertramp debería ser más importante que todo eso...

RUSSEL: Sí, y año tras año me quedo más impresionado de que su música se siga vendiendo bien y siga sonando en las emisoras de radio de todo el mundo. Obviamente, debimos hacer algo bien, pero normalmente a la gente le interesa más lo que hicimos mal. Quiero decir que la naturaleza humana prefiere hacer hincapié en las rarezas y en los escándalos de la vida de los músicos de una banda de rock. Suelen estar envueltos en asuntos de sexo y de drogas, y lo demás resulta aburrido para la gran mayoría de la gente. Todos los miembros de Supertramp llevaban vidas de clase media muy normales, al menos aparentemente. Así que la prensa no podía contar demasiados chismes sobre ellos y por tanto no les resultaban interesantes. Pero también ocurrieron algunas cosas alrededor del grupo que nadie sabe y que tendrán que esperar para salir a la luz, aunque en ocasiones siento una gran tentación de contarlas cuando leo esos cuentos de hadas que se han escrito sobre la marcha de Roger.

TLW: ¿Estás insinuando que la marcha de Roger no se debió a las razones de las que hemos oído hablar todos estos años?

RUSSEL: Esa es una pregunta muy interesante que tal vez sea respondida en un futuro muy cercano...

TLW: Después de tantos años siguiendo la historia de Supertramp, pensaba que lo sabía todo sobre la marcha de Roger: sus discrepancias artísticas con Rick, sus discrepancias personales con la mujer de Rick, el nacimiento de sus dos hijos, los cambios que propuso dentro de la banda y que no fueron aceptados...

RUSSEL: A veces es preferible no saber algo… Sí, todo eso que comentas sucedió realmente, pero hubo otros motivos que jamás han trascendido, en particular el hecho de que Rick actuó sin ninguna lealtad hacia nadie. De todas formas, eso puede cambiar muy pronto, pues le he enviado un correo electrónico a Roger para contarle mi versión de los hechos, quién dijo qué, cuándo y por qué, lo cual no encaja con la versión oficial de la historia. Le he preguntado a Roger si me puede dar alguna razón por la que no debería lanzar al mar este mensaje metido en una botella. Ahora estoy esperando a que Roger me dé permiso para contar todas esas cosas, pues es posible que él prefiera mantener la cámara sellada.

TLW: ¿Sabes por qué Dave Margereson fue despedido como representante del grupo al final de la gira de 1983? ¿Estabais tú y Roger al tanto de ese asunto?

RUSSEL: Para ser técnicamente exactos, Dave fue expulsado durante la última gira, hacia el final de la parte europea y bastante antes de la parte norteamericana. Me lo contó todo en el bar del hotel de Alemania la noche antes de marcharse, y aunque se supone que Roger y yo deberíamos haber dado nuestro visto bueno a esa decisión, en mi caso no supe nada hasta que Dave me lo dijo. Así que, aunque Roger siguió en el grupo tres meses más, es remotamente posible que él tampoco supiera nada. Cosas más raras sucedieron en aquella gira, así que no me sorprendería.

TLW: ¿Fue la falta de beneficios económicos el principal motivo para despedir a Dave?

RUSSEL: El dinero pudo ser un problema, pero en aquel período había una especie de vacío de poder, sin que nadie tuviese el control sobre nada. Aunque los que más control tenían sobre todo eran Rick y Sue, así que creo que echarle la culpa a Dave sería un poco injusto.

TLW: ¿Qué opinión te merece el trabajo de Dave como representante del grupo entre 1973 y 1983?

RUSSEL: Dave fue esencial para el éxito de Supertramp durante los primeros años, ya que tenía contacto directo con A&M gracias a su amistad con Derek Green, el director de la compañía en Londres, y también tenía una relación muy buena con Jerry Moss. Eso nos aseguraba conseguir casi siempre todo lo que pedíamos, además de que Dave conocía a la perfección los entresijos del negocio de la música. Nosotros necesitábamos a alguien que nos diera la libertad suficiente para que aquel proyecto tan frágil y con un equilibrio tan inestable pudiese desarrollarse. El fue, y todavía sigue siendo, un gran apasionado de Supertramp, por lo que le dolió mucho que se deshicieran de él.

TLW: ¿Cómo fue la relación entre Dave y Roger a lo largo de los años?

RUSSEL: Dave siempre intentó que Roger se sintiese cómodo, incluso adquiriendo una casa en Nevada City en un momento dado. La relación de Dave con Rick y con Sue estaba totalmente emponzoñada, pero Roger nunca tuvo ninguna animadversión hacia Dave.

TLW: ¿Por qué crees que la relación de Dave con Rick y Sue acabó siendo tan mala?

RUSSEL: El estilo personal de Dave era muy diferente al de Roger, al de Rick y al mío propio. Eso condujo a muchos conflictos sutiles que con el tiempo se fueron convirtiendo en menos sutiles. Dave tiene una personalidad muy fuerte y no le gusta andar con rodeos, aunque en muchos aspectos es una especie de artista frustrado. El miembro del grupo al que se encontraba más unido era Dougie Thomson, y ninguno de ellos le dedicaba mucho tiempo a lo que percibían como extravagancias de “pedorros del arte” como Roger y, sobre todo, yo. Durante los primeros años, antes de que Sue y Karuna entrasen en escena, Dave tenía una autonomía relativa sobre los temas financieros.

TLW: ¿Qué ocurrió cuando llegaron Sue y Karuna?

RUSSEL: Mi vida y la de Dave se volvieron imposibles. El y yo, aunque de distinta forma, siempre habíamos estado navegando entre Rick y Roger desde el principio. Ellos eran dos personas muy diferentes en todos los aspectos, pero podías negociar con ambos. Sin embargo, cuando te conviertes en la paloma mensajera entre Yoko Ono y Leona Helmsley, estás perdido. Sobre todo si una de ellas tiene una escopeta. Y, tristemente, eso es lo que ocurrió. Sue nunca ha mantenido en secreto el hecho de que nos quería a Dave y a mí fuera del grupo, alegando que ella debía ser la representante. Le costó conseguirlo bastantes años, y sólo habría sido una anécdota divertida si Roger y Karuna no hubiesen decidido subirse a su nave espacial y retirar la escalera, dejando en tierra a los demás y permitiendo que Sue se hiciera con el control absoluto.

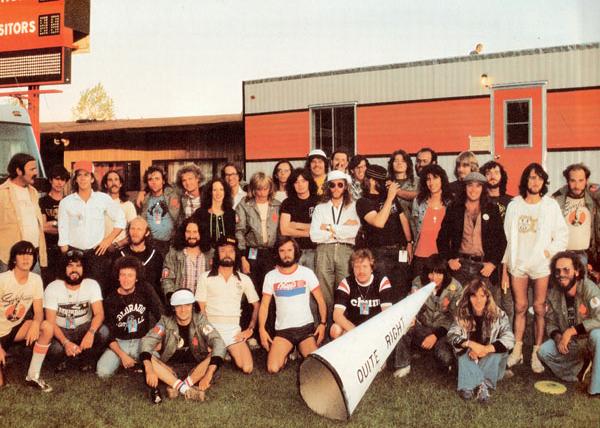

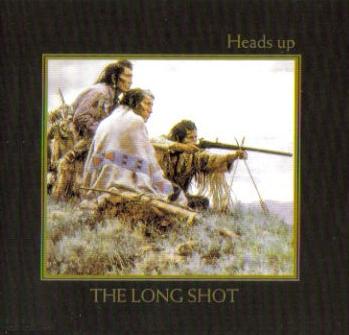

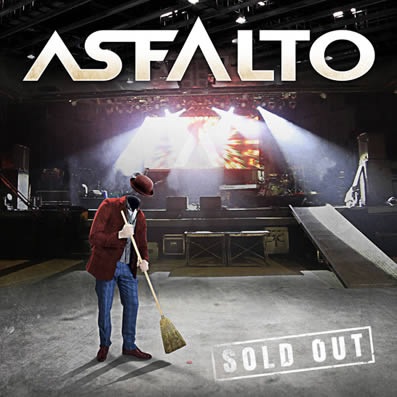

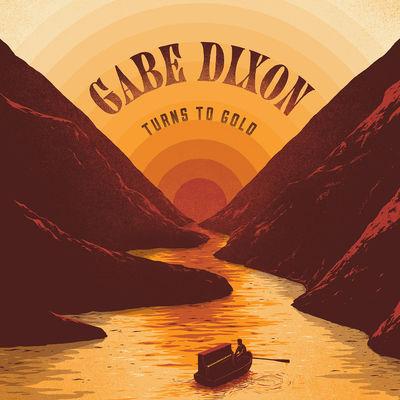

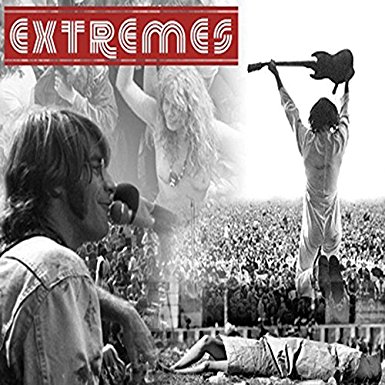

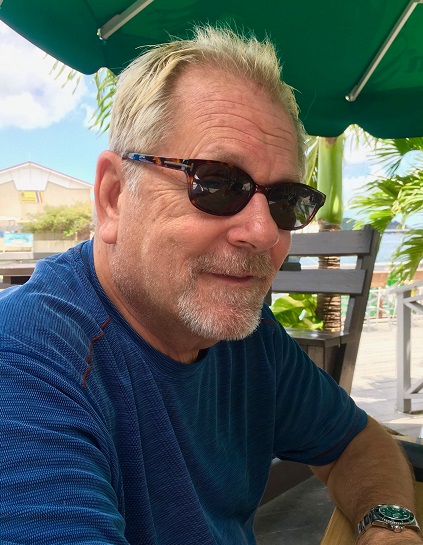

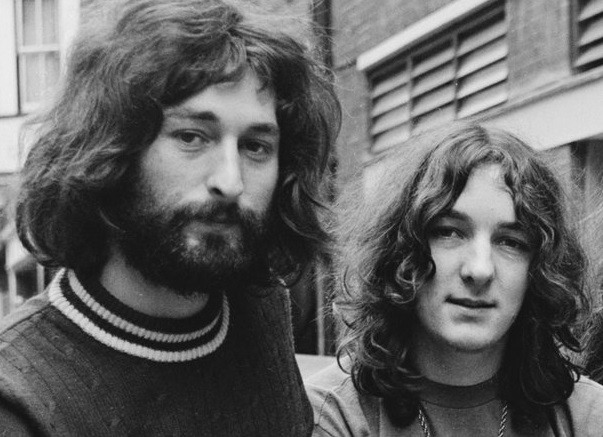

Russel Pope, a la derecha de la imagen, haciendo tiempo en el aeropuerto junto a Bob Siebenberg

y el técnico de luces Tony Shepherd durante una de las giras de Supertramp en los años 70.

Juan Lago and Abel Fuentes had a long chat with Russel Pope, Supertramp soundman from 1971 to 1983, about the history of the band and many other things.

TLW: According to my notes, you were born in Johannesburg, South Africa, on May 9th 1948… Is it right?

RUSSEL: Yes, not my choice. Mine would have been Liverpool and slightly earlier in time.

TLW: Did you study something related to music or sound during your early years?

RUSSEL: I was pretty much addicted to music since 1956 when that Elvis person appeared in the air. I had been in a cover band in South Africa so I knew some basics about sound but I never anticipated being involved in that world so I paid no attention.

TLW: When did you move to England?

RUSSEL: I moved to London on Valentine’s Day 1970 hoping to meet and maybe work with The Beatles. They broke up almost immediately. Change of plans.

TLW: When did you join Supertramp?

RUSSEL: It was December 28th 1970. Rick and Roger shared a moth eaten flat in Maida Vale, West London, no furniture, just a couple of beds. Richard Palmer had just left, reasons unknown to me. Bob Millar quit soon afterwards, the first of many “Spinal Tap” moments to come.

TLW: Was it Davy O’List who first replaced Richard Palmer on guitar?

RUSSEL: I have a vague memory of David O'List being mentioned by Rick in some scathing way, but if he was involved it must have been for about five minutes. Richard Palmer was already gone when I arrived, not a happy departure judging by the Xmas card I saw in the flat at Maida Vale the day I started with them. The card read "Happy Xmas cunts".

TLW: So who was the new guitarist?

RUSSEL: There was no guitarist. The band was a four piece: Roger Hodgson on bass, Rick Davies on organ mostly, Dave Winthrop on sax and flute and Bob Millar on drums. Dave was pretty much the lead singer, Roger sang about a third of the set. Rick didn't sing at all. Very strange line up for a rock band but it worked although the music had no relevance to who they became in later incarnations.

TLW: It seems strange to me that Dave was the main singer in that band, while Roger sang almost every song on the first album... Did Dave sing only Supertramp songs or he also sang songs by other artists?

RUSSEL: Roger was the main singer on the first album but as a four piece with no guitar they were limited in what they could play live from the album. Plus a lot of that record is very precious and delicate and would not fair well in front of a crowd of drunken guys. So they did a few covers, “All along the watchtower” comes to mind, and they did “Try again” and “It’s a long road” from the album which Roger sang. Dave sang “Nothing to show” and the cover songs and just seemed the dominant force at the time. There were a few songs that Dave sang that were staples through 1971, 1972 and the first few months of 1973. They were never recorded for an album although they did show up on assorted BBC live shows like “Old Grey Whistle Test” and “John Peel Show”. “Black cat” was one, “White hot rock” was another… Another planet from who they became later.

TLW: When did Roger begin to play guitar?

RUSSEL: Roger only began to play guitar once “Indelibly stamped” began to take shape a few months later when Frank Farrell appeared on bass. It took even longer for Roger to begin playing the Wurlitzer live, until “Dreamer” showed up, which was the high moment of every show for the next two years or so.

TLW: So Roger took his time to start playing keyboards on stage…

RUSSEL: “Dreamer” was the only keyboard song from Roger until “Hide in your shell” and “If everyone was listening”. Roger was writing songs on piano and harmonium but didn't play them live. He wrote “Breakfast in America” around this time but he only had a little demo of it and it was never played live until it finally made it onto to a record in 1979, which deeply offended Rick's artistic sensibilities as he despised it. Of course his accountant probably likes it a lot as he gets exactly he same royalties from it that Roger gets. All for singing the immortal line "What you got, not a lot". Almost funny.

TLW: Why did you join the band?

RUSSEL: I joined Supertramp as an extra pair of hands to load and unload the van. No more, no less. I was broke, freezing and about to be homeless and somebody said “does anyone want to go to Norway with some band or other for ten pounds a week?”. It was a fortune… I volunteered. Who knew.

TLW: So you participated in the famous “disastrous tour” of Norway… What do you remember about it?

RUSSEL: The infamous Norway expedition started on the 28th December 1970. We took the ferry from Newcastle to Bergen and the first gig was on December 30th on top of a mountain and the audience mostly arrived on skis. At the end of the show they were all screaming drunk and commenced beating the shit out of each other with chairs. The van stayed on that mountain until the spring of 1971 as it expired after getting up the steep climb. The expedition lasted about ten days in a new rented van, ferries and icy roads with 1,000 feet drops into the fjiords. Beautiful, terrifying. All I could think was "what the hell have I done".

TLW: Did you play many shows in Norway?

RUSSEL: We did the infamous top of mountain gig and then Bergen Town Hall on December 31st. Then over the course of about a week we travelled south, took multiple ferries across the fjiords, crossed multiple mountains, did a gig on the island of Haugesund, a large barn as I recall, and then some place in Stavanger, then more mountains, more fjiord ferries and eventually a ship to Denmark and a very long and very cold drive to Paris, via an overnight stop in Hamburg and a very Second World War style delay at the German French border.

TLW: Why did you drive to Paris?

RUSSEL: We had to play a show at H.E.C. University. We made there with about four hours to spare and Sam was like a little kid about it and never gave up the phrase “We have made H.E.C.! Whenever there problems later on he would say “Yes boys, but you made H.E.C.”. Frankly I was overjoyed to make Paris in any form while still alive and I especially liked Sam's choice of restaurants and Sam's credit card.

TLW: What was your main task during your first times in the band? Is it true that you even drove the van?

RUSSEL: I drove the van, froze in the van, slept in the van, loaded and unloaded the van, fixed assorted wiring, tuned the drums, mixed the shows, etc. etc. etc., from early 1971 through September 1974 when “Crime of the century” was ready to be taken on the road with a real budget and an actual crew. I had a helper some of the time here and there and from the summer of 1972 a South African friend who had been in the same cover band joined the circus as my extra pair of hands. That was Tony Shepherd who, like me, accidentally ended up doing something he didn’t ever imagine, in his case the Supertramp light show. He and Roger became very close friends for the next thirty years, along with Ken Allardyce who was the other half of the light show and also extremely accidental in his choice of work.

TLW: Did you have been working as a sound engineer with other bands before joining Supertramp?

RUSSEL: No, I made it up as I went along. Shortly after I was drafted to drive and carry things, Mick Coles, the roadie-in-chief who hired me announced he was going to leave to be the driver for Led Zeppelin’s bass player, a giant step up in the food chain apparently. So the sound job went to whoever was standing closest to the mix console at the time. It happened to be me.

TLW: Do you remember when Dougie Thomson joined the band?

RUSSEL: Dougie appeared sometime in the spring of 1972 as I recall. It might have been slightly earlier. Roger was the bass player when I joined the enterprise, then Frank Farrell, who lasted through “Indelibly stamped” and on to late 1971 or early 1972.

TLW: According to “The Supertramp Book” by Martin Melhuish, you recommended Roger to take LSD when he did it for the first time in July 1972… Is it right?

RUSSEL: I have never read that particular book. A friend I trust advised me not to and I believed him. I did see the cover and it only features four people out of five. That was supposedly the definitive book on the band. I doubt there is a Supertramp fan in the world that would not notice that somewhere, somehow, someone removed Roger. Maybe they were just bad at arithmetic or they forgot?

TLW: On a letter Rick sent to Sam in 1972, he wrote this about you: “Russel, our ever loyal servant, may soon be leaving. He's thought of some incredible scheme to make himself untold millions. He disappears on off days to study 'the plans'. He's going to ask Coca-Cola for 25,000 pounds”... Can you tell me what did he mean?

RUSSEL: Of course the word servant should have been a big clue…It was a mad scheme that involved bringing drive-in fast food places to England, complete with girls on roller skates bringing the burgers, fries and shakes to the cars. Tony Shepherd, his cousin and I had designed a special container for the food that sat on the open car door, the idea being that England was not California so the open trays that were all over the US would not work in the rain, or the freezing English winters. Considering the rain and the freezing English winters it was beyond foolish, but we persuaded ourselves that if Coca-Cola bought the logo space on the containers we could open the first one in six months and retire to the south of France the month after that. And then we wouldn't be servants driving a van all over wet and freezing English roads.

TLW: What do you recall from the time when you were living with the band at 35 Holland Villas Road in London?

RUSSEL: We were at Holland Villas from 1st January through to 1st July 1973. Previously, in 1971 and 1972, Rick, Roger and I had shared various flats in London with assorted understanding women who always seemed to pay the rent. But this house was a rather grand four bedroom palace by our standards. It had a grand piano and busts on pedestals and a long ornate dining room table. It also came with a house keeper, Gladys, and a very unfortunate beagle, called Droopy on account of his legs being so short that his stomach practically hugged the ground.

TLW: How did you manage to rent that grand house, considering that Supertramp had not succeeded by then?

RUSSEL: The house was in Maggie Charles name, who was one of London's in demand models of the time and the older sister of Barbara Charles, briefly Roger's girlfriend, who subsequently married Ken Allardyce, who eventually joined the circus as part of the crew and went on to run the light show with Tony Shepherd. Maggie Charles then briefly became Roger's girlfriend at Holland Villas and much later also married Ken Allardyce. A little confusing I know but everyone ended up happy ever after with their final choices. It was musical chairs in the romance department for a while.

TLW: Is it true that Joe Cocker had lived there?

RUSSEL: Yes, the owners had previously rented the house to Joe Cocker and band and they were horrified at the result and wanted no more to do with rock bands. But Maggie Charles, being a hot model and quick with her wits, persuaded the owners of Holland Villas to rent her and, supposedly, three friends of her who were models too, the house.

TLW: So you paid the rent as if you were just four people although you were many more…

RUSSEL: We quickly filled the four bedrooms, Roger and his sister Caroline in one, Maggie and pre and post Roger girlfriends in another, Nigel and Nicky, who were two Australian friends of Rick, in another and the Bollos, identical Australian twins in the fourth bedroom. Rick lived in the closet/shower on the landing and Tony Shepherd, Ken Allardyce and I moved into the attic, plus 3 girlfriends. There was a pull down ladder in the ceiling of the hallway that let you up into the attic, no windows, no floor treatments, no nothing. We had three mattresses, we hung the required Indian tapestries of the time as partitions, for privacy. So, in total there were fifteen of us at the Holland Villas house.

TLW: And what about the housekeeper? Was she an accomplice of yours?

RUSSEL: Yes, Gladys loved us to death and joined the conspiracy, as did Droopy, who never ate better in his life. Every month there would be an elaborate procedure at rent time when the owners would arrive to collect from Maggie and her three friends who supposedly shared the house with her. All evidence of the rest of us had to be put away, including any instruments, sleeping bags, illegal substances, whatever. The attic ladder would be folded into the ceiling as though it were never used. We did have one episode when they insisted they check the attic for some reason and we had to dismantle our little palace up there in about four minutes flat, very quietly sneaking out while Maggie amused and delayed the owners until the coast was clear.

TLW: What happened inside the band, musically, during that time?

RUSSEL: It was in this period that we came to the end of Supertramp version 2.0. Sometime around Easter we ended up in Copenhagen for a residency at the Revolution Club. I think it was a week but it was Easter and Carlsberg were selling their Easter Beer so I doubt anyone remembers. The Danes thought it was hilarious to give the stupid English the Easter Beer because the formula was approximately 2 Easter Beers = 1 Coma. It was on the way back to London that Dave Winthrop abruptly announced that he was quitting and he just walked away at a motorway cafe, never to be seen again. No explanation, no nothing. I put it down to the Easter beer. Back at Holland Villas, I vividly remember Kevin Currie coming to collect the drums and there being a dispute about that issue. Rick and Roger decided pretty quickly to put Kevin out of his misery and we just went into suspended animation.

TLW: So it seemed that Supertramp had disbanded at last…

RUSSEL: Yes. Tony and I started renting ourselves and the old Sam sound system out and pretty soon ended up with Steeleye Span and headed to America with them for the month of July for a Jethro Tull tour. In Los Angeles, just off stage at the Forum, I bumped into Wilf Wright from Chrysalis, the agent who had booked most of Supertramp's gigs so far. He asked after the band and I told him it was pretty much extinct for now. He waved his hand around at the 20,000 people and said “They were a good little band but of course Supertramp could never have done this”. Things like that stick in the brain for a long time. But when Tony and I came back from the US at the end of July Rick and Roger had already held one rehearsal with Bob and John, and the band had resurrected.

TLW: And soon afterwards, late 1973, all of you went to live at a farmhouse called “Southcombe”, to change the fate of the band…

RUSSEL: Yes, all of us, including wives, girlfriends and even Dougie and Christine's cat, TC. It was an idyllic winter fantasy with A&M paying all the bills and everyone in a space where anything was possible and we just knew it was all going to work out and everyone was going to be happy ever after. It was almost fun walking to the pub a mile away in deep snow and stepping on cow turds.

TLW: Is it true that the soundman Norman Hall was also living with you there, though he was not a member of the crew yet?

RUSSEL: Yes. Norman did not join the crew until the first tour which started in September or October 1974 at The King's Road Theatre with a showcase for A&M. He had been a flatmate of Rick's in Shepherd's Bush and was persuaded to become Bob Siebenberg's drum tech. One or two years later he became my "assistant" after Kenny Thomson graduated to stage manager and then re graduated to tour manager for the Chris de Burgh person. Much later Norman was the designated soundman for Rick and Sue's band.

TLW: What was the best sound system used by Supertramp when you were in the band?

RUSSEL: Except for the very beginning we only ever used one sound system with Midas consoles and Martin speakers. I think I had the first Midas console ever made, as early as 1971 and then three more over the years. Roger and I did a full demo of “Crime of the century” at the farmhouse on that first console. Switzerland Sam was the money man in those years and he was eccentric to say the least but very generous and he clearly adored the band and their music. He withdrew sometime in late 1972, forgiving a debt of some sixty thousand pounds.

TLW: Why did you decide to use that sound system?

RUSSEL: We saw Pink Floyd perform “Dark side of the Moon” in London in 1973 and I was amazed to hear a live show sound that fucking good. They were also using Midas consoles but their speaker system from Martin Audio was enormous. So when “Crime of the century”’s budget appeared I went straight to Dave Margereson and said “I’ll have whatever Pink Floyd are using thank you very much”. That system allowed us to reproduce “Crime of the century” at shows in a way that reproduced the sense of awesome power that orchestral songs need to have to really affect people in a visceral way. It was very expensive and worth every damn penny. Later on some people spent that much money and much more on “important” things like first class air travel, silly long cars and silly expensive hotels. Different priorities.

TLW: Was that sound system better to play in inside venues or open air?

RUSSEL: The best sound was always in smaller inside venues, preferably concert auditoriums or theatres. The acoustics were very similar to a studio, reasonably dead without a lot of splash and clatter from concrete walls and miles of steel seats which is the way sports arenas are built. Outdoor shows could be fantastic but basic physics meant you had to have a huge amount of power to make up for all that open space. When shows grew to 50,000 and up it became increasingly difficult to sustain the grand majestic qualities and still make it sound intimate and warm. Pink Floyd never had that problem because their stuff was so orchestral and somewhat abstract. Supertramp mostly played little middle class pop songs and they had to sound just like the records because that was what people had come to expect from them. Most of the time it worked beautifully but occasionally, not so much.

TLW: What producer did you prefer to work with, Ken Scott or Pete Henderson?

RUSSEL: Ken Scott came from The Beatles and Abbey Road although I did not know he was from Beatle Land until we were already in the studio with him. I totally fell in love with “Hunky Dory”, the David Bowie album before “Ziggy Stardust” and I vowed that if we ever had the chance Ken Scott should be the first and only choice for “Crime of the century”. I more or less annoyed Dave Margereson for months about the issue until he made the arrangements for Ken to mix a single, “Land ho”, which did not go well and we almost blew the opportunity. Fortunately the demo we did at the farmhouse persuaded Ken to think again and voila.

TLW: Why did you replace Ken with Pete?

RUSSEL: After “Crime of the century” and “Crisis? What crisis?” it was decreed that a change was necessary and we asked Geoff Emerick , the “Sgt. Pepper” engineer, to do “Even in the quietest moments”. Hey, when in doubt think Beatles… Geoff was not available and he suggested that his protégé Peter Henderson do the basic tracks at Caribou Ranch and then Geoff would do the overdubs and mixing at Record Plant in Los Angeles. Pete had just done the “Wings” album with McCartney so it seemed like a grand idea. Pete flew to Los Angeles and we all met him at some wacky new age restaurant in Topanga Canyon. We were slightly nonplussed to meet what seemed to be a teen age boy. Needless to say it took about ten minutes to overlook the youth issue and Pete became part of the extended family, a relationship that continues to this day.

TLW: When did you leave Supertramp?

RUSSEL: It was September 25th 1983, when “Famous last tour” tour ended.

TLW: What have you been working on since then?

RUSSEL: Studying the feeding habits of the California squirrel. And producing and engineering for some indie artists I like from time to time.

TLW: In the summer of 2006 you worked at Cups’N’Strings studios on the restoration of the master tapes of Paris 1979 show… What can you tell us about it?

RUSSEL: Actually I just collected the tapes, delivered the tapes, collected the digital results and shipped them to Pete Henderson. Just like 1971, drove the truck, loaded and unloaded the truck, etc. Full circle.

TLW: Is it true that those tapes had been found in Bob Siebenberg’s farm and were covered by cow dung?

RUSSEL: I like to think so, it’s such a good story and has inspired a lot of comment.

TLW: Do you know why they were there?

RUSSEL: Bob just “acquired” a whole pile of master recordings of all the shows we recorded on the Breakfast tour in 1979. He recorded over them for his solo projects. Somehow no-one ever questioned this or thought to peer into the future. I was long gone and so was Dave Margereson.

TLW: It was said then that you also were working on the filming of that show to edit a DVD… Is it true?

RUSSEL: No.

TLW: Do you think it could be released soon?

RUSSEL: I know nothing about that.

TLW: Roger Hodgson said recently that he is ready to play again with Supertramp… Would you work with Rick Davies and him again if they asked you for?

RUSSEL: I don’t believe they asked me. The Beatles are more likely to reform in either case.

TLW: Are you still in touch with other Supertramp members?

RUSSEL: No.

TLW: Who was your best friend in the band?

RUSSEL: Midas console #2.

TLW: What do you think about many people called you “the sixth member of Supertramp”?

RUSSEL: When the accountants say it I like it a lot.

TLW: You are an open book on Supertramp history… Are you sure that you don't want to write your own book?

RUSSEL: It might be amusing but it would come from a very different place than most fans would want to hear. I think that would cause some discomfort in certain quarters. I have a great deal written but to no real purpose. I have always said that there are probably ten people in Canada and three in France who could care about it.

TLW: Why do you think so?

RUSSEL: Supertramp lacked any identifiable star in the conventional rock band sense so they were kind of anonymous. And the others were always afraid that too much attention would go to Roger so there was an active and intentional effort to avoid any cult of personality. Being relatively anonymous has shielded them from any real spotlight on who was who, who did what to who and all the usual back story to a very successful band. Plus, no heroin, no trashing hotel rooms, virtually no groupies. It wasn't milk and cookies but it wasn't debauchery by anyone's standards and therefore probably extremely boring. Plus everyone has seen “Spinal Tap” so all you have to do is change the names and... bingo.

TLW: But Supertramp’s legacy in music would be more important than that…

RUSSEL: Yes, and I am utterly amazed year after year at the fact the music is still selling and on the radio around the world. Obviously we did something right but the more interesting stuff is usually what we did wrong. I mean, it's human nature to focus on the weird and scandalous elements of musicians lives. Where rock bands are concerned most of that revolves around sex and drugs. The normal boring parts of their lives hold no interest for most people. Supertramp were terminally normal and led very ordinary middle class lives unless you scratch the surface. So there wasn't much gossip for the press and therefore no real story, at least by most media standards. That stuff may have to wait a while longer although I am sorely tempted sometimes when I read the fairy tales of Roger's departure.

TLW: Are you insinuating that Roger's departure was not due to the reasons they talked of along the years?

RUSSEL: That is a very interesting question and one that may be answered in the very near future…

TLW: After so many years following Supertramp history, I thought I knew everything about Roger's departure: artistic discrepancies with Rick, personal discrepancies with Rick's wife, birth of his two children, non-accepted changes in the band proposed by him...

RUSSEL: Sometimes it's better not to know... All of those happened, it's just that there are other events that have never surfaced, particularly the idea that Rick acted out of loyalty to anyone. Anyway that may change soon because I sent an email to Roger to tell him my version of all that happened surrounding those events, who said what, when, for what reasons and none of it matched the official story in any way. I asked Roger if he could give me any good reasons why I should not let it float out to sea in a bottle. Now I am waiting for a response from him before I say anything else as he may wish to leave the vault sealed.

TLW: Do you know why Dave Margereson was fired as manager of the band at the end of 1983 tour? Were you and Roger aware of this?

RUSSEL: To be technically accurate, Dave was ejected during the last tour, towards the end of the European leg but well before the US and Canada section. He told me in the hotel bar in Germany the night before he left and although they would have technically required both me and Roger to sign off on that decision I know I was not even aware of it until Dave told me. So although Roger was still there for three more months it is remotely possible that he was not consulted either. Stranger things happened on that tour so that would not surprise me.

TLW: Was the lack of profits under his management the main reason for firing Dave?

RUSSEL: The money was an issue but there were was such a vacuum of power in that period that no one really had control of anything and Rick and Sue had more than anyone else, so I think blaming Dave is a little unfair.

TLW: What do you think about Dave’s management from 1973 to 1983?

RUSSEL: Dave was essential to Supertramp's success in the early years as he was deeply connected to A&M through his friendship with Derek Green, the head of the company in London, and he also had a very good relationship with Jerry Moss. This ensured that we got everything we asked for most of the time and Dave understood the nuts and bolts of the music business very well. We needed someone to buy us the freedom to allow us to indulge our somewhat fragile and delicately balanced enterprise. He was and still is passionate about Supertramp and was deeply wounded when he was disposed of.

TLW: How was the relationship between Dave and Roger along the years?

RUSSEL: Dave always tried to accommodate Roger, even buying a house in Nevada City at one point. Dave's relationship with Rick and Sue was totally poisonous but Roger never had any personal animosity towards Dave.

TLW: Why do you think that Dave’s relationship with Rick and Sue became so bad?

RUSSEL: Dave’s personal style was very different than Roger's, Rick's and mine. That led to a lot of subtle conflict that became less subtle over time. Dave has a very strong personality and he is very much a no nonsense guy, although he was really a frustrated artist in many ways. The person in the band he most bonded with was Dougie Thomson. Neither of them had too much time for what they perceived as artsy fartsy preciousness from Roger and especially from me. For the first few years, before Sue and Karuna appeared, Dave had relative autonomy on the business side of things.

TLW: What happened when Sue and Karuna appeared?

RUSSEL: Dave's life, and mine, became impossible. We had both, in different ways, always been navigating between Rick and Roger since the beginning. They were utterly different people in every way. You could negotiate successfully with Rick and Roger but when you are the carrier pigeon between Yoko Ono and Leona Helmsley you are pretty much doomed. Especially if one of them has a shotgun. And sadly, that is what we were dealing with. Sue had never made a secret of the fact that she wanted Dave and me gone and that she ought to be the manager. It took her many years and it would have a laughable prospect if Roger and Karuna had not been so determined to climb into a spaceship and pull up the ladder, leaving everyone stranded and Sue free to take control.

Russel Pope, at the right, in an airport with Bob Siebenberg and lighting engineer Tony Shepherd during a Supertramp tour in the 70s.